The Impact of Sleep Deprivation on Unhealthy Belly Fat: Research Reveals the Connection

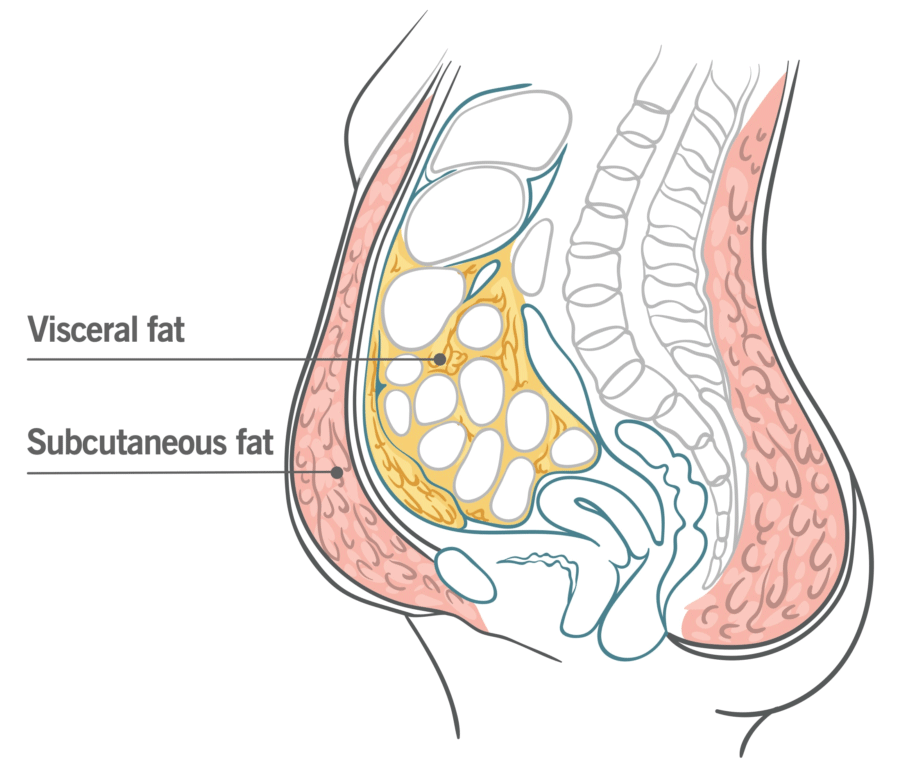

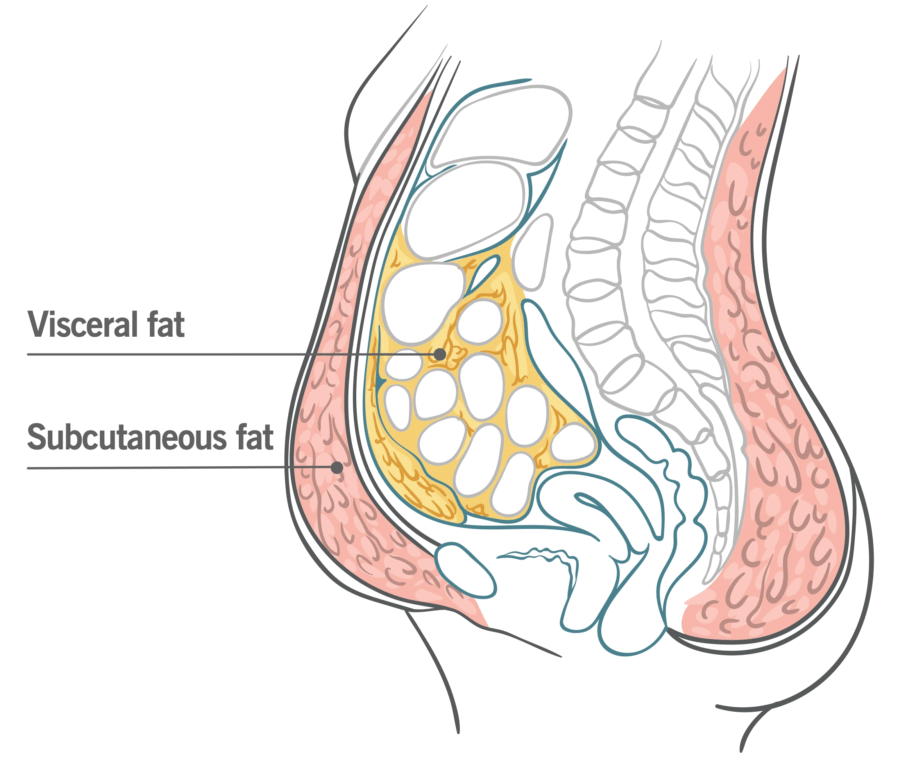

Research indicates that inadequate sleep in combination with unrestricted food access increases calorie consumption and subsequent fat accumulation, particularly unhealthy belly fat accumulation. Results of the study indicated that inadequate sleep led to an increase of 9% total abdominal fat area and 11% visceral abdominal fat relative to a control sleep group – visceral fat is deep-seated within abdominal organs that is strongly associated with metabolic and cardiac diseases.

Sleep deprivation has become an increasingly prevalent behavior of choice in America. Over a third of individuals in this country fail to receive sufficient restful slumber due to shift work and using smart devices and social networks at the usual times of restful slumber. Furthermore, when awake for longer without engaging in physical activity increases food consumption may increase as well.

Results have shown that reduced sleep duration among healthy young individuals leads to an increase in caloric intake and weight gain; as well as an increase in belly fat accumulation.

Fat is normally stored subcutaneously; however, due to lack of sleep it appears that more of it was distributed viscerally where it may become unhealthy and potentially dangerous. Even during recovery sleep there was some weight reduction; however visceral fat continued increasing significantly.

Lack of sleep appears to be an unacknowledged trigger of visceral fat deposition and that short-term catch-up sleep won’t reverse its accumulation, with long-term lack of sleep being linked with obesity epidemic, metabolic diseases and cardiovascular illnesses.

The study involved 12 healthy obese-free participants participating in two 21-day sessions within an inpatient environment, separated by a 3-month washout period. After random assignment to either a normal sleep control group or restricted sleep group for 1 session each (and vice versa on subsequent occasions), each was randomly allocated a sleep position during one session before switching groups for subsequent ones.

Each group in this study had access to free choice food throughout. Appetite biomarkers; fat distribution (including visceral and/or belly fat); body composition; body weight; energy expenditure and energy intake were measured and monitored throughout.

In the initial four days of this experiment, individuals were permitted to sleep 9 hours each night in their beds during an acclimation phase. Restricted sleep group individuals were limited to 4 hours while control group individuals maintained 9 hours over 2 weeks; both groups then experienced three recovery nights with 9-hour nights for full recovery.

Over 300 additional daily calories were consumed during sleep restriction duration, including approximately 13% more protein and 17% more fat compared to acclimation stage consumption levels. Consumption increases peaked in early sleep deprivation days before levelling off in recovery phase back towards starting levels; energy expenditure was generally unchanged throughout.

Visceral fat accumulation was only detected through CT scanning; otherwise it would have gone undetected, since weight measurements alone would have given a false sense of security regarding potential health ramifications from lack of sleep. Furthermore, any prolonged insufficient rest periods could contribute to visceral fat increases over time and result in progressive and cumulative visceral fat increases over time.